Someone emails your office. Or tags your organization on Facebook. Or replies-all to a PDF you published.

“This is wrong.”

It might be one field in one table. One stale phone number. One address that changed. One capacity figure that was always a best guess. But what happens next is bigger than the correction. Suddenly, everything you publish gets questioned. Not because your team is careless, but because your readers have no way to tell what is confirmed, what is inferred, and what is missing.

That is the credibility cliff. And most teams fall off it the same way: not with bad data, but with unclear certainty.

A lightweight confidence labeling system fixes this without turning your life into a compliance program. It works for local governments publishing maps and dashboards, nonprofits maintaining community directories, and small teams juggling messy multi-source information with limited staff and high expectations.

The goal is not perfect data. It is trustworthy data.

The real problem: users assume all fields are equally true

When you publish information, readers flatten nuance.

A value copied from a PDF looks as true as something measured in the field. A number derived from a formula feels just as authoritative as a number verified last week. Even when you know the backstory, your audience cannot see it.

Blank fields cause their own trouble. Many people interpret missing data as “they did not care” or “they are hiding something.” Sometimes it is simply “we do not know yet,” which is a completely normal state for real-world data.

The fix is simple: communicate uncertainty explicitly, consistently, right where the data is being read.

A simple confidence model (start here)

Start with three labels. You can put them on a webpage, a PDF, a spreadsheet, a dashboard, or even a printed handout.

Verified

Confirmed by a trusted source, with a date. “Trusted” means you can name the source category and you know when it was confirmed.

Estimated

Derived or inferred, with a short method note. It is not a secret guess. It is a documented estimate.

Unknown

Not available, not provided, not yet collected, or not applicable.

That is enough for most teams.

If you need a little more nuance, add one or two optional labels:

User-reported

Provided by a third party and not yet verified. Useful when you accept submissions from businesses, residents, or partner organizations.

Outdated

Known to be stale but kept for context, flagged clearly so it does not masquerade as current.

If you are tempted to create seven labels, stop. If people cannot remember them, they will not use them. A system that no one uses is worse than no system at all.

Add two small fields that change everything

The confidence label is the headline. Two tiny metadata fields are what make the system actually work in practice.

Last verified date

Example: “Verified on 2026-01-06”

Source note

Short, human-readable: “County GIS”, “Broker email”, “Field visit”, “Public PDF map”, “Utility provider”, “State database”

Why these work so well:

- Dates create a shared reality about freshness. A reader may not love that something is six months old, but they can understand it. And they can stop assuming it was verified yesterday.

- Sources reduce arguing and speed troubleshooting. When someone disputes a value, your team no longer has to reconstruct the origin from memory. You can route the question to the right place fast.

How to label “Estimated” responsibly (without misleading)

“Estimated” is where many public-facing datasets get into trouble, because teams use vague language that sounds confident but is impossible to audit.

You can avoid that by making your estimates method-first.

Use wording like:

- “Estimated via proximity to trunk line”

- “Estimated via historical listing data”

- “Estimated via owner statement”

- “Estimated via capacity report (2024)”

- “Estimated from comparable facilities in region”

In other words, the estimate is not only a number. It is a number plus a traceable reason.

What to avoid:

- “Approx.” with no method. Approximate compared to what?

- “Likely” unless you define why. Likely based on what evidence?

- Passive fog. “It is believed that…” by whom?

A good test: if a reader challenges an estimated value, can you explain the method in one sentence without scrambling? If yes, label it Estimated and move on. If no, it is probably Unknown until you have a real basis.

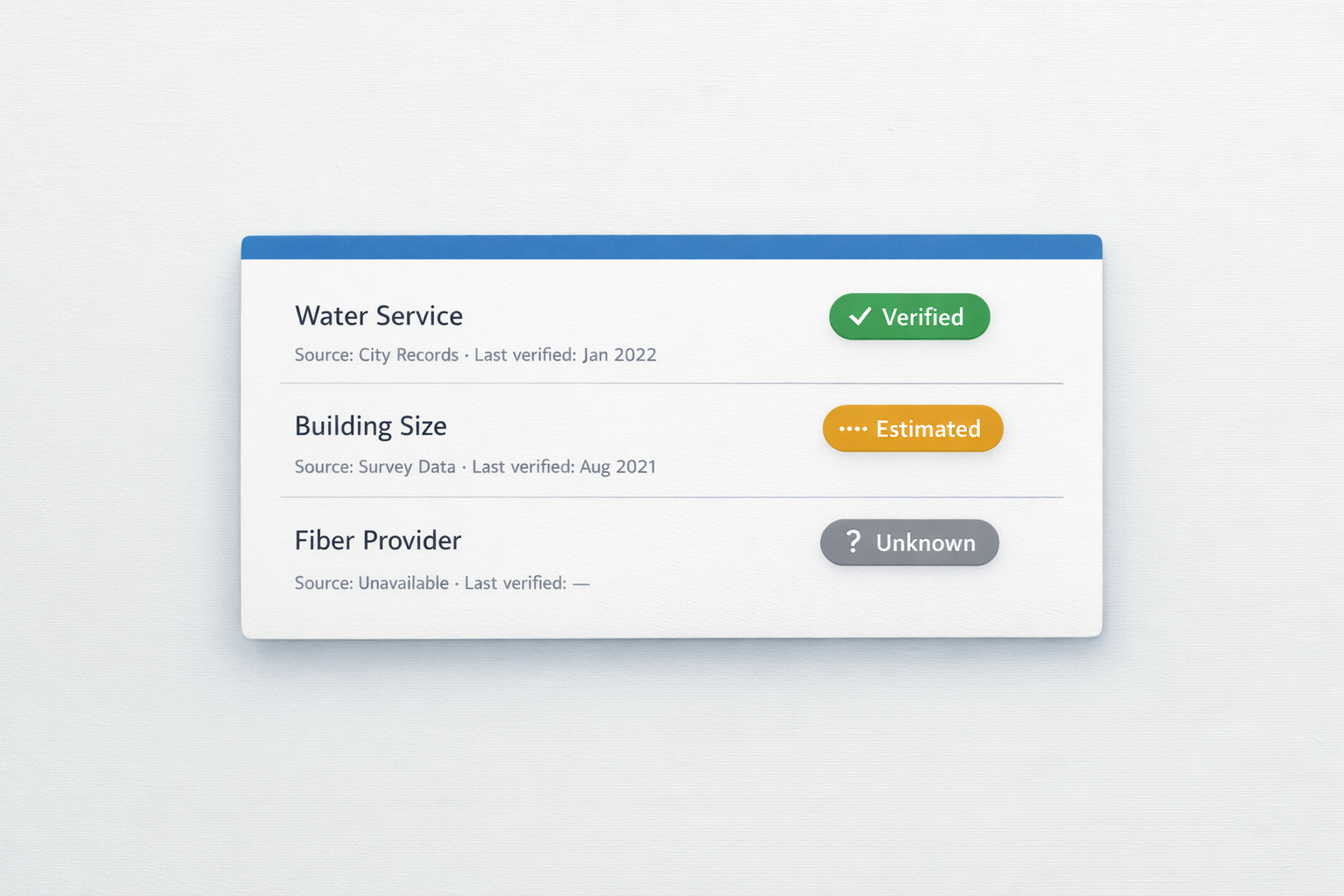

A public-facing display pattern that works

Confidence should be visible at the point of reading, not hidden in an appendix.

A simple display pattern:

- Field value

- Small badge: Verified / Estimated / Unknown

- Tooltip or footnote: source + date + (optional) method

Examples:

- Water service: Available (Verified)

Tooltip: County GIS, verified 2026-01-06 - Building size: 82,000 SF (Estimated)

Tooltip: Estimated from prior listing, last checked 2025-09-12 - Fiber provider: Unknown

Tooltip: Not provided by provider, last reviewed 2025-12-01

You can implement this in a web UI with badges and tooltips, or in a PDF with a small label and a numbered footnote, or in a spreadsheet export with a Confidence column. The medium does not matter. Consistency does.

The internal workflow (keep it lightweight)

The biggest fear is that labeling will create bureaucracy. It does not have to. The internal workflow can be simple enough to run with a small team.

A minimal operating process:

- Only staff can mark Verified. This protects the label and keeps it meaningful.

- Anyone can propose User-reported. This is how you accept updates without letting unverified claims look official.

- Unknown is acceptable. If a field is not critical, it is better to be honest than to force a guess.

- Maintain a small verification queue. Not everything needs attention. Focus on high-impact fields.

What counts as “high-impact” depends on your domain, but a good generic rule is:

High-impact fields are the ones that change decisions, money, safety, compliance, or public controversy.

If a wrong value would cause someone to waste a trip, waste a budget, miss a deadline, or publish an accusation, that field belongs in the verification queue.

Avoid these common mistakes

These are the failure modes that quietly kill confidence systems:

- Too many confidence levels. People stop using them or apply them inconsistently.

- No dates. Confidence decays silently, and you end up overstating freshness.

- Trying to verify everything. You burn time and still fail, because data changes faster than your capacity.

- Using labels as an excuse to publish unreviewed claims. “Estimated” is not a shield for sloppy work. It is a promise that you have a method.

Keep your system small, visible, and honest.

A starter template you can copy today

If you want to implement this immediately, start in a spreadsheet. This tiny schema works for almost any dataset:

- Field

- Value

- Confidence (Verified / Estimated / Unknown)

- Source

- VerifiedDate

- Notes/Method

Even if you never publish the full table, maintaining these columns internally will improve your outputs. Your PDFs get easier to defend. Your dashboards get easier to maintain. Your staff spend less time in circular arguments about who said what.

Trust scales better than perfection

Most organizations do not lose trust because they made one mistake. They lose trust because readers cannot see the difference between confirmed facts, reasonable estimates, and unknowns. When everything looks equally certain, every correction feels like a scandal.

A confidence labeling system replaces that dynamic with something calmer and more adult:

“We know this, we estimate that, and we do not know this yet.”

If you publish public-facing data, try adding confidence, a last verified date, and a source note to your next update. Then pay attention to what changes: fewer disputes, faster corrections, and a better relationship with your readers.

If you already publish data, what is the hardest field for your team to verify consistently?